A bit of history

Sitting between Europe and Africa, due to Sardinia and Sant’Antioco’s strategic position and rich mineral reserves, tidal waves of power-hungry invaders run to its shores; its precious natural resources (silver and lead) together with a fertile arable land have long made the island a target of the Mediterranean’s big powers. The first foreigners on the scene were the enterprising, sea-faring Phoenicians (from modern-day Lebanon).

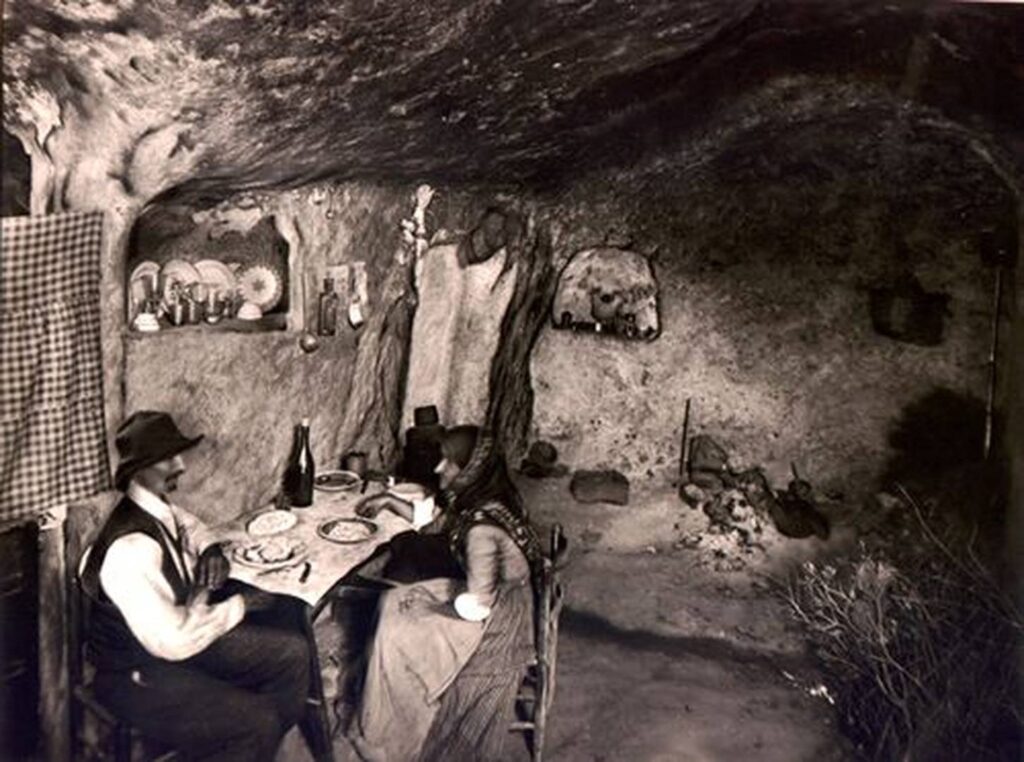

But in the early years (8000 BC to 3000 BC), Sardinia was home to several thriving tribal communities. The island would have been a perfect home for the average neolithic family – it was covered with dense forests that were full of animals, there were caves for shelter, and land suitable for grazing and cultivation. Underlying everything were rich veins of obsidian, a volcanic black stone that was used for making tools and arrow tips.

One thing is certain: Sardinia’s mysterious, unfathomable nuraghi reveal a highly cultured civilisation. The nuraghic people were sophisticated builders, constructing their temples with precisely cut stones; they travelled and exchanged (as revealed by the discovery of seal remains and mussel shells inland); and they had the time, skills and resources to stop and build villages, and to dedicate to religious workship and arts such as ceramics and jewellery.

Some historians argue that the nuraghic populace of Sardinia were the Shardana (people of the sea), a piratical seafaring people who appear in early Egyptian inscriptions.

Back to the Phoenicians, it semms that, at least in the early days, they lived in relative harmony with the local nuraghic people, who seemed happy enough to leave the newcomers to their coastal settlements – Karalis (Cagliari), Bithia (near modern Chia), Sulci or Sulki (modern Sant’Antioco), Tharros and Bosa. However, when the outsiders ventured inland and took over the lucrative silver and lead mines in the southwest, the locals took umbrage.

The Phoenicians appealed to Carthage for aid. The Carthaginians were happy to oblige and joined Phoenician forces in conquering most of the island. Most, though, not all. As the Carthaginians found out to their cost, and the Romans would discover to theirs, the tough, mountainous area now known as the Barbagia didn’t take kindly to foreign intrusion. More tangible vestiges of the Phoenicians are visible in Sant’Antioco’s historic centre, littered with necropolises and with an intact tophet, a sanctuary where the Phoenicians and Carthaginians buried their stillborn babies. Monte Sirai near Carbonia also offers a glimpse into the island’s past with its ruined Phoenician fort, the first inland fortress built in 650 BC, following clashes with Sardinians.

In 216 BC the Carthaginians are defeated by the Romans, who build roads and develop centres at Karalis (Cagliari), Nora, Sulcis, Tharros, Olbia and Turris Libisonis (Porto Torres), and in Sulci/Sulcis/Sulky (Sant’Antioco) as well, a such important city to get authorized to coin money.

In reality, the ambitious Roman Republic faced two main challenges to its desire to control the southern Mediterranean: the Greeks and the Carthaginians. The Romans saw off the Greeks first, and then, in 241 BC, turned their attention to Carthaginian-controlled Sardinia. The Romans arrived in Sardinia buoyed by victory over Carthage in the First Punic War (264–241 BC). But if the legionnaires thought they were in for an easy ride, they were in for a shock. The new team of the Sards and their former enemies, the Carthaginians, were in no mood for warm welcomes, and faced them fiercely, with bloody clashes. Anyway once they had Sardinia in their hands, the Romans set about shaping it to suit their own needs. Despite endemic malaria and frequent harassment from locals, they expanded the Carthaginian cities, built a road network to facilitate communications and organised a hugely efficient agricultural system.

After the fall of the Roman empire, a time jump leads us to the Byzantine era. With its rich natural resources and absentee Byzantine rulers, Sardinia made for an inviting target and the island was repeatedly raided in the 9th and 10th centuries. But as Arab power began to wane in the early 11th century, so Christian ambition flourished, and in 1015 Pope Benedict VIII asked the republics of Pisa and Genoa to lend Sardinia a hand against the common Islamic enemy. The ambitious princes of Pisa and Genoa were quick to sniff an opportunity and gladly acquiesced to the pope’s requests.

Curiosity:

When Homer wrote about hero Odysseus smiling “sardonically” when being attacked by one of his wife’s former suitors, he was surely alluding to a grin in the face of danger. Yet the word sardonic, from the Greek root sardánios, has come to mean simply “scornful” or “grimly mocking” in today’s usage. If recent scientific findings are anything to go by, Homer may have been on the right track with his hint at danger. Studies carried out by scientists at the University of Eastern Piedmont in 2009 identified hemlock water dropwort (Oenanthe crocata) as being responsible for the sardonic smile from, of course, Sardinia. It seems that in pre-Roman times, ritual killings were carried out using the toxic perennial (known locally as “water celery”). The elderly, infirm and indeed anyone who had become a burden to society were intoxicated with the poisonous brew, which made their facial muscles contract into a maniacal sardonic grin, before being finished off by being pushed from a steep rock or savagely beaten. Regardless of whether the word sardonic refers to this sinister prehistoric malpractice, it seems that the findings could have positive implications in the field of medicine. The head of Cagliari University Botany Department, Mauro Ballero, believes that the molecule in hemlock water dropwort could be modified by pharmaceutical companies to have the opposite effect, working as a muscle relaxant to help people to recover from facial paralysis.

Carthaginians, Romans, Aragonese and Pisans – all have left their indelible stamp on Sardinia. Thanks to a certain inward-looking pride and nostalgic spirit, the Sards have not allowed time and the elements to erase their story. Travellers can easily dip into the chapters of the island’s past by exploring tombs, towers, forts and churches.

Another time jump, up until 1410 Sardinia was split into four provinces: Logudoro in the north west, Cagliari in the south, Arborea in the west and Gallura (meaning rooster or cock from the Latin Gallus) in the north east.

At that time (Giudicati – provinces), for much of the 300-year period between the 11th and 14th centuries, the island was fought over by the rival mainlanders. Described as Sardinia’s Boudicca or Joan of Arc, Eleonora d’Arborea (1340–1404) was the talismanic figure of Sardinia’s medieval history and embodies the islanders’ deep-rooted fighting soul.

Sardinia’s Spanish chapter makes for some grim reading. Spanish involvement in Sardinia dates back as far as the early 14th century. In 1323 the Aragonese invaded the southwest coast, the first act in a chapter that was to last some 400 years.

Piedmontese rule (from 1720, until Italian unification in 1861) was no bed of roses, either, but in contrast to their Spanish predecessors the Savoy authorities did actually visit the areas they were governing. The island was ruled by a viceroy who, by and large, managed to maintain control.

Sardinia was granted autonomy in 1948.

Sardinia’s rich mineral reserves were being tapped as far back as the 6th millennium BC. Obsidian was a major earner for early Ozieri communities and a much sought-after commodity. Later, the Romans

and Pisans tapped into rich veins of lead and silver in the Iglesias and Sarrabus areas. By the late 1860s there were 467 lead, iron and zinc mines in Sardinia, and at its peak the island was producing up to 10% of the world’s zinc. But however much material conditions improved, the life of a miner was still desperately hard, and labour unrest was not uncommon. Mining output remained high throughout Italy’s post-WWII boom years, but demand started to decline rapidly in the years that followed.

Although Isola di Sant’Antioco has been inhabited since prehistoric times, the town of Sant’Antioco was founded by the Phoenicians in the 8th century BC. Known as Sulci/Sulcis/Sulky, it was Sardinia’s industrial capital and an important port until the demise of the Roman Empire more than a millennium later. It owes its current name to St Antiochus, a Roman slave who brought Christianity to the island when exiled here in the 2nd century AD. Evidence of the town’s ancient past is not hard to find – the hilltop historic centre is riddled with Phoenician necropolises and fascinating archaeological finds.

DON’T MISS:

The great little museum Ferruccio Barreca, in Sant’Antioco town, is one of the best in this part of southern Sardinia. It displays artefacts spanning millennia of ancient history, including a superb collection of pint-sized nuraghic bronzetti (bronze figurines) which, in the absence of any written records, are a vital source of information on Sardinia’s mysterious nuraghic culture (approximately 1800–500 BC), terracotta amphoras and pottery, jewellery. The museum takes a chronological spin, deftly moving from pre-nuraghic times to the Bronze and Iron Ages, the Phoenicians and Romans.

Sant’Antioco Basilica: hidden behind the modest baroque facade is a sublimely simple 5th-century church. To the right of the altar stands a wooden effigy of St Antiochus, a martyr of North African origin who was enslaved by the Romans and later hid out in the basilica’s creepy catacombs. Accessible only by guided tour, the catacombs consist of a series of burial chambers, some dating back to Punic times, that were used by Christians between the 2nd and 7th centuries.

Some 500m from the town’s Museo Archeologico, the tophet is an 8th-century-BC sanctuary where the Phoenicians and Carthaginians buried their still-born babies. Before visiting, it’s worth checking out the tophet display at the Museo Archeologico to see how the tombs were laid out.

Also known as the Forte Sabaudo, this 19th-century Piedmontese fort marks the highest point in Sant’Antioco town.

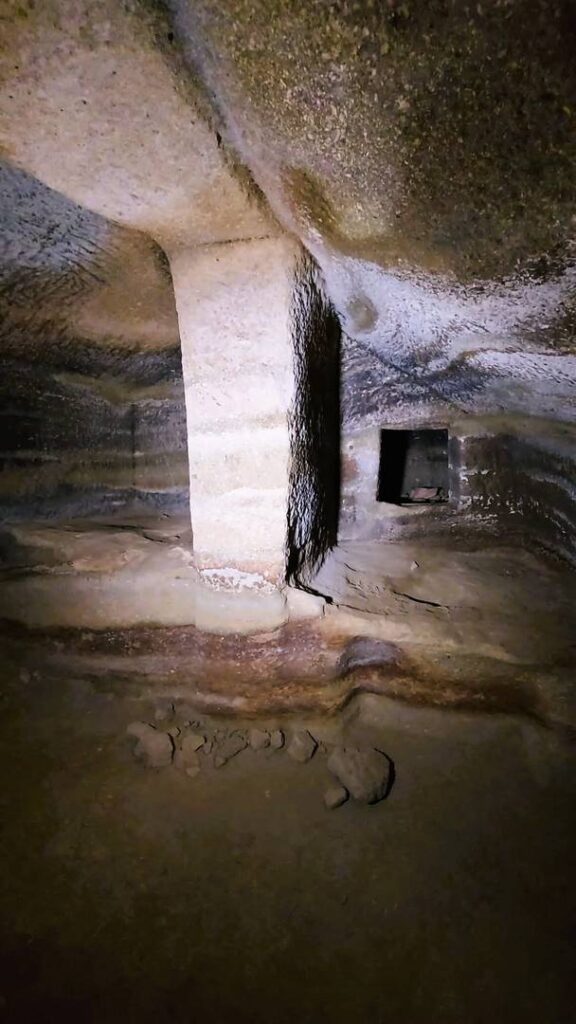

Nuraghes: There are some 8000 of these bee-hive like towers on Sardinia, (some of which are over twenty meters in height), more than 30 in Sant’antioco island, however only a fraction of the estimated 30,000 that used to be in existence. These pre-historic monuments can be as old as 3500 BC but to this day nobody is quite sure what they were built for. Religious temples, ordinary dwellings, rulers’ residences, military strongholds, meeting halls, craft workshop, or a mix of them are all contenders. These enduring architectural enigmas are still unsolved. The island is scattered also with Bronze Age towers and settlements, tombe dei giganti (‘giant’s grave’ tombs), domus de janas (‘fairy house’ tombs) and pozzi sacri (sacred wells). Visit Grutti Acqua nuragic site, with its nuraghic lake, a short distance from Erbe Matte Agriturismo and Glamping.

Iglesias: The Iberian atmosphere of Iglesias and its collection of churches make it a fascinating place to explore. Although named after its churches – Iglesias means churches in Spanish – the town has a long history as a mining centre hearth.

Necropolis di Montessu: A prehistoric cemetery set in a rocky amphitheatre, one of Sardinia’s most important archaeological sites, this ancient necropolis in the verdant countryside near Villaperuccio.

Revisit the Bronze Age at Unesco-listed Nuraghe Su Nuraxi, in the heart of the voluptuous green countryside near Barumini, one of the island’s most visited nuraghe.

Explore Nora Phoenician and Roman history in an ancient town on a peninsula near Pula and Cagliari. A former village of indigenous Sardinian, soon became an emporium, then a Phoenician city, Carthaginian later, and finally a crucial Roman crosswords and port. Dive (if you can) or go snorkeling and admire Roman roads and Nora submerged ruins.

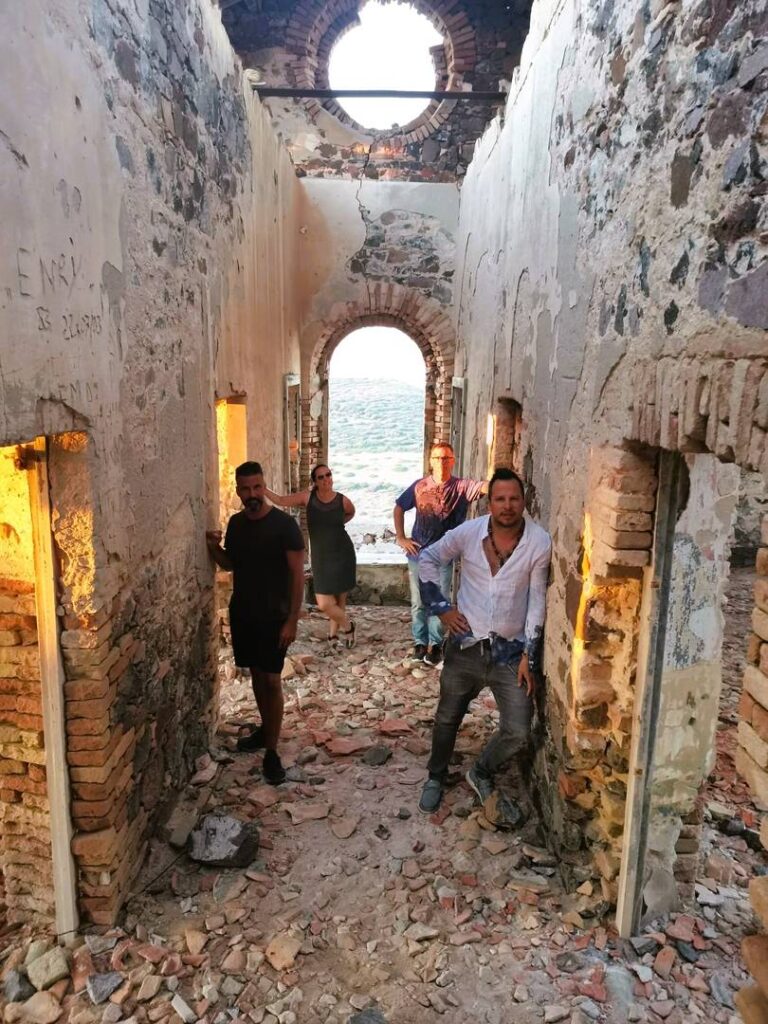

Semaforo di Capone Sperone, only a mile away from Erbe Matte farmhouse and glamping, just a pleasant walking: although much of the original historical construction has been cannibalised for building material, enough has survived to pique the imagination, and the view from here is really breathtaking. Keep at hand cell phone and camera.

Poking around Roman ruins at the beautifully sited Tempio di Antas, north of Iglesias, an impressive Roman temple set in bucolic scenery 9km south of Fluminimaggiore, it has stood in isolation since the 3rd century AD. Built by the emperor Caracalla, it was constructed over a 6th-century-BC Punic sanctuary, which was itself set over an earlier nuraghic settlement. In its Roman form, the temple was dedicated to Sardus Pater, a Sardinian deity worshipped by the nuraghic people as Babai and by the Punic as Sid, god of warriors and hunters.

A remnant of Buggerru’s day as a mining centre, the Galleria Henry is a 1km-long tunnel that was dug in 1865 to allow a small train to transport minerals from underground depots to washing plants. A highlight of the hour-long gallery tour (now a turistic train which enter and exit the massive rocks, in a fascinating way) is the view down to the sea just 50m below. Ask for visit time.

Tratalias was once the religious capital of the entire Sulcis area, The church today presides over Tratalias’ lovingly renovated borgo antico, the medieval part of town which was abandoned in the 1950s after water from the nearby Lago di Monte Pranu started seeping into the subsoil. Consecrated in 1213, this lovely church is a prime example of Sardinia’s Romanesque Pisan architecture. Non always open to visit, ask for advice.

The Villaggio Minerario Rosas, near Narcao, is a fascinating museum complex housed in what was once an important lead, copper and zinc mine: it hosts music events, entertainments, food&wine tasting.